Climate change is compounding the debt crisis in developing countries. UNCTAD spells out the actions necessary to safeguard the world’s sustainable development ambitions.

© Tobin Jones/UN Photo | The city of Jowhar in drought-hit Somalia, which is one of the countries listed by the International Monetary Fund as being “in debt distress”.

The world cannot afford inaction in the face of the overlap of public debt and climate change, according to a recent UNCTAD report entitled “Tackling debt and climate challenges in tandem: A policy agenda”.

The report cautions against “a vicious cycle of perpetual vulnerabilities and economic stagnation” across indebted economies on the front lines of climate change.

It calls for improved access to financing for vulnerable countries, on terms conducive to ensuring both debt sustainability and long-term development needs.

It puts forward a multilateral policy agenda to propel climate-resilient structural transformation in the world’s vulnerable economies.

The report says such policies “should start with a reform of the international debt architecture, and scaling up public-led, affordable development financing for climate investments.”

Unsustainable debt in times of climate emergency

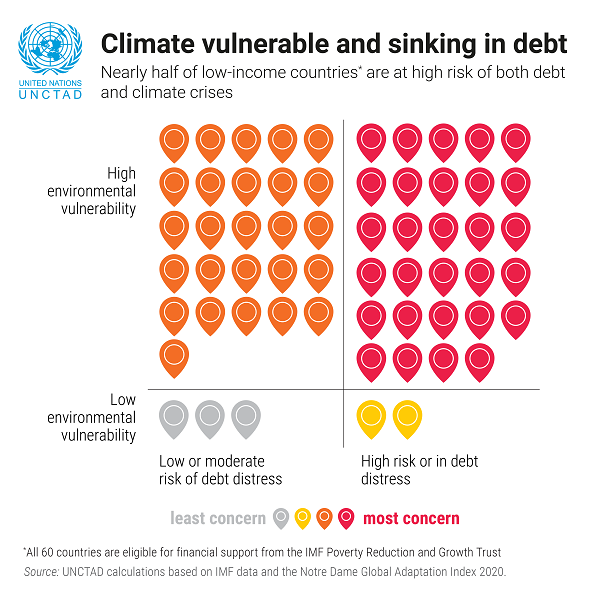

Currently, 29 out of 69 poorer countries eligible for concessional finance under the Poverty Reduction and Growth Trust (PRGT) of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) are at the intersection of high debt and climate vulnerabilities.

But this overlap is not limited to PRGT-eligible economies, for which the IMF discloses the risk of debt distress, meaning a country is not able to repay its debts.

Several lower-middle-income nations such as Sri Lanka and Lebanon, which have both defaulted on their debts, are also climate vulnerable.

Overlapping threats, inadequate financing

The report spotlights mutually reinforcing challenges facing developing economies, including rising investment needs for climate action, unstainable public debt and consequent underinvestment.

While climate-related shocks – such as droughts and floods – are becoming more frequent and brutal, developing countries’ ability to cope is heavily impaired by growing debt burdens and limited fiscal space.

Currently, over 70% of public climate finance takes the form of debt and is primarily channelled into climate mitigation.

Meanwhile, the UN Environment Programme estimates that annual adaptation needs for developing countries could amount to $340 billion by 2030, and $565 billion by 2050.

With losses and damage from climate change adding more pressure on government budgets, external borrowing generally grows in the aftermath of a climate shock.

But as UNCTAD Secretary-General Rebeca Grynspan has pointed out, the world lacks an effective system to deal with debt.

“The existing debt architecture is not fit for purpose,” the report says. “It is unable to facilitate both the mobilization of adequate development financing and an orderly and timely resolution of debt crises.”

How to reform the global debt architecture

The report identifies three ways to incorporate climate considerations into a reformed international debt architecture.

Firstly, it calls for a multilateral legal framework for sovereign debt restructuring and relief. It should enable temporary standstills, stays of litigation and lending into arrears to protect debtor countries’ ability to meet their economic, social and human rights obligations during a crisis.

Participation in such a multilateral framework should be allowed for all countries facing debt challenges – independent of the income level – and incentivized through the provision of debt relief linked to a debt sustainability assessment that incorporates long-term financing needs, including for the achievement of the 2030 Agenda and the Paris Agreement on climate change.

Secondly, it urges the establishment of a publicly accessible registry of debt data for developing countries. This would strengthen debt management, reduce the risk of debt distress and help expand environmental, social and governance financing.

Thirdly, it calls for the adoption of climate-contingent debt instruments to allow for automatic, temporary suspension of debt payments, after an indebted country suffers a climate disaster causing damage over pre-defined thresholds.

How to shore up development finance

The report also proposes multilateral initiatives to help close the development finance gap.

It recommends the establishment of an intergovernmental tax forum to help countries stem illicit financial flows and better mobilize domestic resources.

It calls on developed countries to boost existing official development assistance (ODA) commitments with additional resources targeting climate adaptation.

Special Drawing Rights (SDRs) also have the potential to bolster development finance, with innovative mechanisms such as a new general SDR allocations to respond to ongoing global crises.

The report also calls for greater efforts to raise the capital base of multilateral and regional development banks, given their crucial role in providing development finance on concessional terms.

UNCTAD recommends using the UN Multi-Vulnerability Index (MVI) as a criterion for concessional lending, where debtor countries borrow internationally on more favourable terms than in the marketplace.

Compared to income thresholds, MVI aims to capture all dimensions of vulnerability – economic, social and environmental – and considers countries’ resilience to external shocks.