By Jan Hoffmann, Head of Trade Logistics, UNCTAD

A container ship in the port of Valencia, Spain. © Jan Hoffmann

Containerized shipping underpins the transport and delivery of global manufactured goods, including inputs, parts, components and consumer goods.

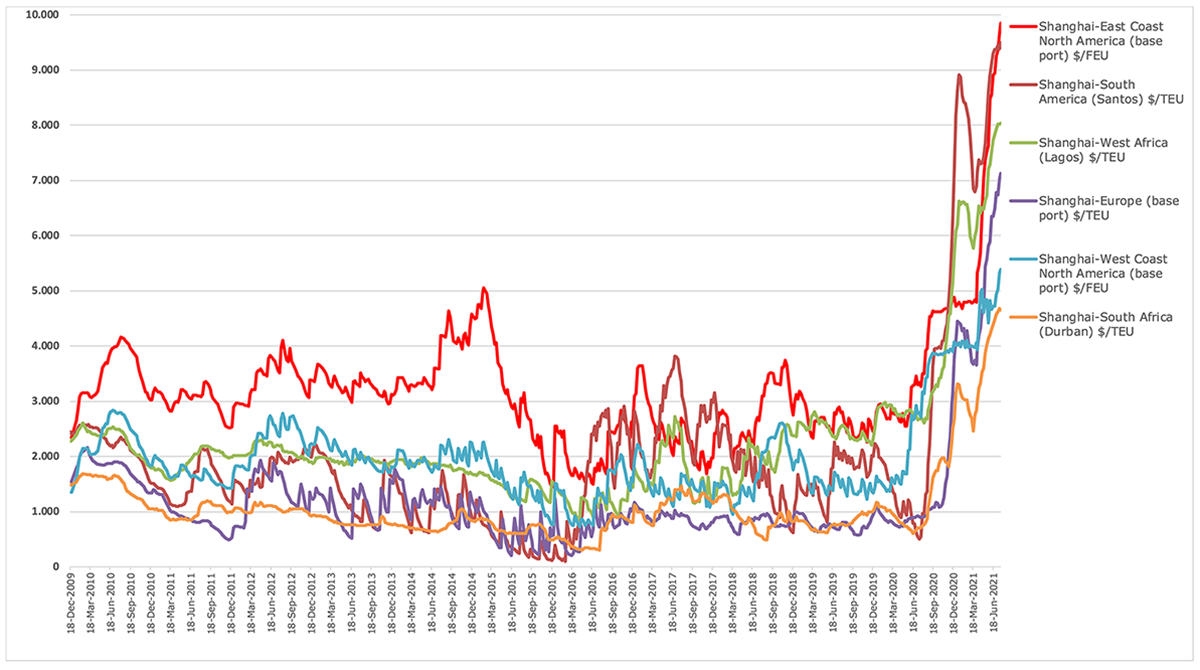

On the heels of the COVID-19 pandemic and its aftermath, the cost of shipping containers has reached historical highs (see figure).

The cost of shipping one standard 20-foot container from Shanghai to Brazil, for example, is today nearly five times higher than the average of the last 12 years.

Shanghai Containerized Freight Index (SCFI), weekly spot rates. 18 December 2009 to 23 July 2021, selected routes

The surge in freight rates and surcharges in container shipping are occurring in tandem with reduced service reliability, a key performance metric for shippers and supply chain managers.

Factors straining maritime supply

A set of COVID-19 pandemic-induced factors have combined to cause the strain on the maritime supply chain currently underway in the liner shipping industry.

First among them is the unexpected and unprecedented swift rebound in containerized trade enabled by an early and rapid recovery in China. This is coupled with massive policy support measures in the United States and Europe that supported household income and expenditure, growth in e-commerce and increased pharmaceutical and home-office purchasing requirements.

Second, the turnaround time for containers, trailers, and ships in ports and intermodal transport links is slower than normal, as ports, transport providers and shippers have to comply with health regulations and social distancing.

Third, supply capacity is not growing fast enough to catch up with demand and the ability of ports to adjust is more constrained than that of shipping lines.

These factors have exacerbated congestion in key ports and shipping nodes, increased delays, reduced visibility of shipments, increased fees and surcharges, added blank sailings, increased overall shipping costs and amplified trade frictions.

One positive development is the high profitability for liner shipping operators.

What does this mean for the consumer?

The high freight rates have a direct impact on the import price of goods, and to the extent that costs are passed on to the consumer, also on the final price in the shop.

Just to get an idea of the order of magnitude, and the range of values, the spot freight rates can be compared to indicative retail values.

Depending on the type and value of goods, the current level of freight costs is equivalent to values between 0.35% of the retail value for high-value clothes and 63.55% for low-value high-volume furniture.

How long will this last?

How long will it take freight rates to return to earlier low averages? There are several medium- and longer-term trends suggesting freight rates will likely remain higher than the previous long-term average for several years.

For more than a decade, liner shipping companies had confronted very low freight rates. To survive, unit costs needed to be reduced. To reduce unit costs, carriers invested in ever-bigger (economies of scale) and newer (more fuel-efficient) ships.

However, the older ships were not scrapped, and the overcapacity remained, keeping freight rates low. This situation has now changed to a market with no overcapacity, and although the current order book for new ships is growing again, it takes time to build these ships.

Smaller and more vulnerable economies already pay more for shipping

UNCTAD has extensively assessed the determinants of international maritime transport costs. Our analysis shows that small and vulnerable economies are also confronted with higher international transport costs.

For example, a typical small island developing state pays on average twice as much for the transport of its imports than the typical developed country.

The reasons include diseconomies of scale, lower levels of port and trade facilitation performance, higher distances and trade imbalances – situations where ships arrive full but return mostly empty.

What can be done?

Carriers, ports and shippers were all taken by surprise by the pandemic, and the subsequent shortage of empty containers observed since late 2020 is unprecedented. No contingency plans were in place to pre-empt the lack of availability or to mitigate its negative impacts.

Given current trends, several months will likely pass before this disruption can be absorbed across the maritime supply chain and before the system resumes smoother operations.

In the meantime, there are three key considerations for policymakers, to help reduce the likelihood that similar situations will occur in the future:

-

Trade facilitation and digitalization for resilient supply chains. The pandemic has highlighted the importance of resilient supply chains. Customs officials, port workers and transport operators have recognized the need to reduce physical contact, while at the same time keeping ships moving, ports open and cross-border trade flowing.

Some of the trade facilitation solutions proposed by UNCTAD contribute to facilitating trade and transport while protecting the population from the virus. Many of the measures depend on the digitalization of trade procedures, including in maritime transport.

-

Tracking and tracing. The recent shortage in containers and maritime equipment took stakeholders by surprise. Monitoring of port calls and liner schedules, along with better tracing and port call optimization, are among the issues covered by the growing field of maritime informatics.

UNCTAD is monitoring developments through the Review of Maritime Transport series, dedicated publications and online statistics. Policymakers need to promote transparency and encourage collaboration along the maritime supply chain, while ensuring that potential market power abuse is kept in check or prevented.

-

Competition in maritime transport. Carriers have earned high rates of return during the pandemic, with double-digit operating profits for some container carriers in 2020.

Shippers have emphasized that they don’t have access to empty containers for exports and face blank sailings, as well as high freight rates, and competition authorities are investigating potentially abusive behaviours.

While there are several reasons that may explain the shortage in containers and ship supply capacity, including the disruptive nature of the pandemic and associated restrictions, it’s also important to ensure national competition authorities can monitor freight rates and market behaviour. Policymakers should continue to strengthen national competition authorities in maritime transport and ensure they are prepared to provide the requisite regulatory oversight.

In conclusion, it’s critical to ensure strengthened and improved collaboration across the maritime supply chain, with all players working together to enhance efficiency, transparency and reliability, while maintaining a profitable operating environment for liner shipping companies, ports and inland transport providers.

* This commentary is based on ongoing work for the Review of Maritime Transport report.