A new study presented at the WTO's 11th Ministerial says countries' rules for determining a product's origin are increasingly similar, which is good news for the global trading system.

The thousands of rules of origin used by countries and trade blocs to determine if an imported product is eligible for preferential treatment or subject to a trade restriction have in the past been widely divergent. But a new study by UNCTAD and European University Institute researchers shows a growing trend toward convergence.

Such a finding may breathe fresh air into multilateral negotiations on rules of origin, which have been sidelined by the perceived inability to find common ground.

UNCTAD economist Stefano Inama, one of the authors, presented the study, titled Rules of Origin as Non-Tariff Measures: Towards Greater Regulatory Convergence, at an event held in Buenos Aires on the sidelines of the World Trade Organization's Eleventh Ministerial Conference (MC11).

Although deliberations on rules of origin weren't on the agenda at MC11, the WTO has been dealing with the issue since the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade was signed in 1947.

"Despite multilateral attempts within the World Customs Organization, UNCTAD and, most recently, the WTO, it has proven impossible to reach consensus on a multilateral discipline on rules of origin for the last half a century," Mr. Inama said.

Although progress towards convergence hasn't been possible though formal negotiations at the WTO, the study shows that for some products it has "naturally" happened between the rules of origin contained in different free trade agreements.

"We have to take this information to the public – that such progress exists and that we can build upon it," Mr. Inama said.

"We have to break the kind of ‘curse’ that exists on rules of origin."

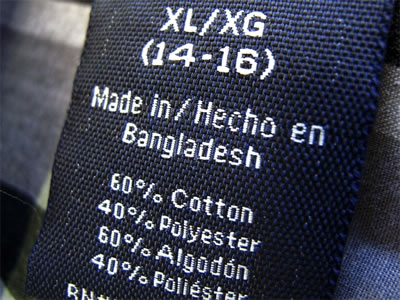

In a completely open global trading system, in which all goods are treated equally, rules of origin would be unnecessary, Mr. Inama said. But the reality is that countries treat products differently based on where they are made.

Governments may use discriminatory trade policies to favour products from the same region, for example, or to promote certain sectors in specific economies, such as manufacturing in the 47 structurally disadvantaged least developed countries (LDCs).

A government may also wish to enforce trade "remedies" to sanction products from a country it believes is playing unfairly. Such remedies often take the form of anti-dumping custom duties.

"The problem is that there are more than 200 free trade agreements, each with its own rules. And this has a cost for businesses that must try to comply with tens of thousands of different rules," Mr. Inama said.

When goods are mostly produced in one country, determining where they come from is easy, Mr. Inama said. But in today's global production systems, which often cross many borders and seas, most of what we buy is built from components that are first made in various countries around the globe.

"Take the iPhone for example," Mr. Inama said. "It may say made in China on the cover because that's where the final product is assembled. But it was designed in California, the camera was made somewhere else, maybe India, and the glass screen was probably manufactured in South Korea."

"This is why rules of origin have become more complex over the years," he said. "The average set of rules of origin for a trade agreement is about 60 pages of technical codes."

There are different ways to determine whether a product "originates" in a specific country. But often the requirement is that a certain percentage of the good's final value is added in that nation, or that the good has undergone a change of customs classification, or a new manufacturing method or process before leaving the country.

"Everyone is negotiating their own rules of origin, but when you look more in detail across the various texts you see that though the rules are not identical they are similar," Mr. Inama said.

The study by UNCTAD and the European University Institute examined five specific rules of origin: the WTO’s draft harmonized non-preferential rules of origin and those included in the Trans-Pacific-Partnership, the Canada-European Union Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA), the EU-South Korea free trade agreement, and the US-South Korea free trade agreement.

"The WTO’s draft harmonized non-preferential rules of origin was selected because it's the only multilateral draft that exists on the issue," Mr. Inama said.

The Trans-Pacific-Partnership was included because of its size, even if its entry into force as originally envisaged is unlikely following the withdrawal of the United States of America. And researchers decided to examine the free trade deal between Canada and the European Union because it’s the first agreement that brings together the North American and European models for rules of origin.

"The negotiated rules of origin can be seen as a kind of compromised text between the two models," Mr. Inama said.

Finally, the US-South Korea and EU-South Korea agreements were chosen because they are two of the latest free trade area agreements signed by the US and the European Union with the same country, with which both have substantial trade flows across different sectors.

The preliminary results of the study show that there is indeed convergence in “non-sensitive” sectors such as chemicals, though the rules continue to diverge in sectors that countries consider to be strategic, such as textiles and clothing for the US, and fisheries for the EU.

"How to build on these similarities remains to be seen, but the important thing is that we have identified convergence," Mr. Inama said. "That’s because people are starting to give up, as if negotiations on rules of origin are doomed to fail."

"The message has to go out that there is convergence; there is a ray of light," he said.

Based on the ongoing research, UNCTAD and the European University Institute plan to publish next year a model protocol on rules of origin to show at a product-specific level where there is convergence or divergence, and to provide options for drafting the rules.

This “pinnacle” of best practices, Mr. Inama said, could be useful during international negotiations, or serve as a guide for governments and businesses during their rules of origin talks when establishing new free trade agreements.

"The overall objective is to build on the convergence and provide guidance in the unchartered territories of rules of origin," Mr. Inama said. "Such an analysis and tool has so far been lacking as an input into the multilateral deliberations at the WTO and World Customs Organization."