Good management of organic residues, a renewable resource, is often overlooked but constitutes a powerful tool to improve livelihoods and tackle plastic pollution.

© Shutterstock/Kehinde Olufemi Akinbo | UNCTAD and partners support projects in developing nations that help convert pineapple waste into textile-grade fibres, promoting the circular economy and empowering communities.

Circular economy potential: Organic waste drives sustainable development and a circular economy.

Plastic pollution: Waste separation reduces plastic pollution and creates economic value.

Empowering communities: UNCTAD and global partners drive projects to help small businesses turn waste into jobs and value.

Plastics, increasingly viewed as the future of fossil fuels, are dominating global discussions on sustainability and environmental degradation. As one of the leading UN-led conferences on plastic pollution convenes to create a legally binding international agreement, UN Trade and Development (UNCTAD) highlights the untapped potential of organic residues in combating plastic pollution and driving sustainable development.

Organic waste, whether from plants, animals, households, or industries, is often poorly managed, leading to pollution that exacerbates environmental and human health and represents lost opportunities for economic use. The UN Environment Programme reports that agriculture and waste (together with fossil fuels) account for most of the human-caused methane, about 60% of which is from wastewater, landfills, livestock manure and rice farming.

A wasted opportunity to combat plastic pollution?

UNCTAD has analyzed trade flows under the Global System of Trade Preferences (GSTP), revealing that residues and waste from the food industry rank as the third most traded agricultural product amongst developing countries.

This trend highlights their growing importance in South-South trade and their untapped potential to foster a circular economy and advance sustainable development.

“Regrettably, organic material and plastics are often mixed, and this lack of separation robs us of value addition opportunities,” says Henrique Pacini who leads UNCTAD’s work at the Sustainable Manufacturing and Environmental Pollution (SMEP) programme, a strategic partnership between UNCTAD and the UK Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (UK-FCDO).

Developing countries face a dual challenge: inadequate infrastructure for managing both organic and plastic waste. This often prevents them from unlocking the potential value of recycling plastics, or transforming organic waste into biogas, alternative proteins, compost or biochar, which could be achieved with proper material separation.

A crucial step in tackling these challenges is the separation of organic and plastic waste, which paves the way for a circular approach. Properly managed, organic residues can be reimagined not as waste but as renewable resources for environmental regeneration.

By bridging these gaps, developing countries could create opportunities for sustainable growth, reduce pollution, and position themselves as innovators in transformative solutions.

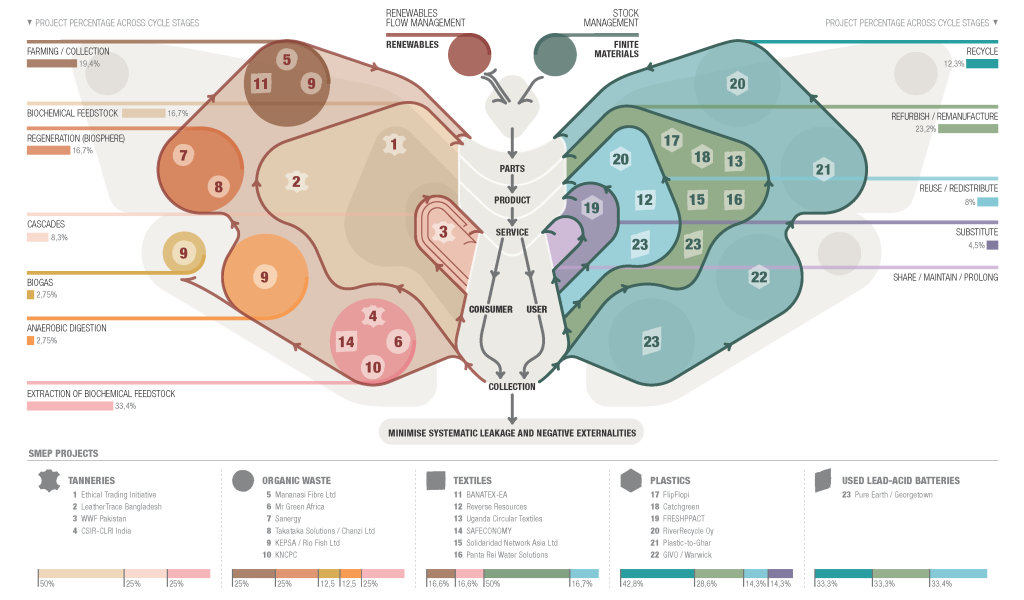

The Butterfly Diagram: Turning circular solutions into actions

On the ground, the UNCTAD-UK FCDO SMEP Programme is implementing scalable, evidence-based solutions in developing countries. It integrates trade, innovation, and sustainability across material cycles, including organic and plastic waste. The programme supports small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) by helping them adopt innovative solutions, expanding markets and improving access to waste management technologies.

Focusing on closing the loop on organic residues, these projects tackle local waste challenges by transforming waste into plastic substitutes and alternative materials. They also reduce methane emissions and open burning, decreasing plastic pollution through incentivised waste separation and decreased reliance on plastics.

SMEs are increasingly at the forefront of turning waste into value-added products, offering affordable alternatives for fertilisers, feedstocks and energy sources, while creating jobs in waste collection, processing and manufacturing.

In Kenya, several SMEP projects are leading the organic waste-to-wealth transition : (i) a company converting pineapple waste into textile-grade fibres (alternatives to synthetic fibres) and nutrient-rich compost (Mananasi Fibre Ltd); (ii) an Earth Shot Prize-finalist turning organic waste such as bagasse and mango and avocado processing waste into biochar for regenerative farming practices (Sanergy); and (iii) a team piloting the conversion of organic waste into Black Soldier Fly (BSF) larvae products, which replaces animal feed and produces biochar and compost for soil regeneration (Taka Taka Solutions and Chanzi). These examples demonstrate the business case for the wider adoption of circular solutions and improved manufacturing processes.

Bringing the circular economy Butterfly Diagram to life

In Kenya, SMEP-supported organic waste projects are showcasing how circular economy principles can benefit communities. By transforming organic residues into valuable products, these initiatives create jobs, empower marginalised groups, and promote sustainable practices.

The successful implementation and impact of the Butterfly Diagram ultimately depend on efficient material separation, strong governance and its human dimension: improving human health, job creation and economic opportunities that lead communities’ engagement and the propagation of circular practices.

At its core, it is not just resource flows – it’s a vital step toward reducing reliance on plastics, cutting pollution at its source, and generating economic value. Failing to address organic residues means missing a critical opportunity to tackle the plastic crisis through solutions already within reach.

Butterfly Diagram: Making the circular economy a reality through practical SMEP solutions