UNCTAD's Trade and Development Report 2020 warns that the global economy has grown more fragile, marred by deeper inequalities.

Minimum wage employee in a fast food kitchen / ©Seika

The world should tackle hyper-inequality to build back a better global economy from the devastation caused by the coronavirus pandemic, according to UNCTAD’s Trade and Development Report 2020.

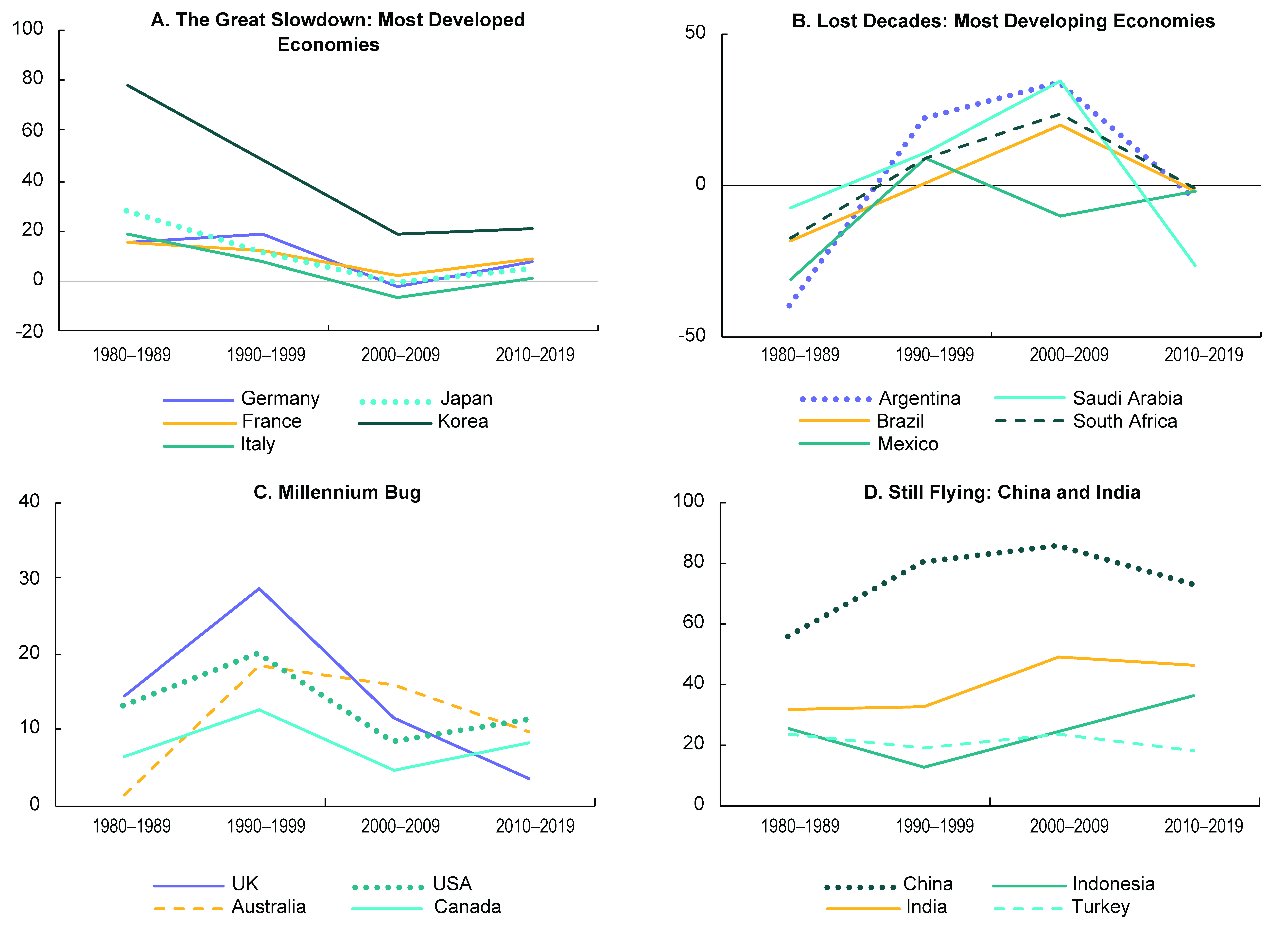

Of all the pre-existing conditions exposed by the COVID-19 shock, hyper-inequality – the product of four decades of wage repression (see Figure) – poses the biggest threat.

The report warns that talk of a “K”-shaped recovery is already pointing to the prospect of an even more unequal future, with a “v-shaped” recovery for the wealthy and a struggle for everyone else.

Building on long-standing research, UNCTAD worries that polarization is now hard-wired into the hyperglobalized growth model in both developed and developing countries.

It argues that tackling this problem must go beyond calls to “leave no one behind” and look instead at how policy choices pick winners and threaten to block a more inclusive recovery.

The global financial crisis revealed the extent to which the financial industry had come to dominate policy and business decisions while fuelling unreliable and unsustainable growth.

“Change was promptly promised but the rules and practices governing the distribution of income and economic power have remained largely the same,” said Richard Kozul-Wright, UNCTAD’s director of the division on globalization and development strategies.

According to the report, the channelling of almost a trillion dollars a year by S&P companies to stock buybacks, rather than investment, is a measure of just how rigged the rules of the game have become, while the prevailing policy mix has favoured rising asset prices only adding to the problem.

Figure: Real wage growth, selected countries, 1980–2019 (10-year percentage point changes)

Fragile global economy, marred by inequalities

As a result, by early 2020 the global economy had grown more fragile, marred by deeper inequalities, soaring debt and a fractured multilateral governance.

UNCTAD says the COVID-19 pandemic provides a second chance to recover better but unless there is a dialling back of regulatory capture by corporations and inequalities are reduced, the global economy will become even more fragile and the damage from the next shock will be even more profound.

The report shows that focusing on trade growth or foreign direct investment fails to address the underlying “rules of the game” that frame the inequality challenge.

While both stalled after the global financial crisis, free trade agreements, tax havens, strict intellectual property regimes, shell companies, share buybacks and monopsony power continued to squeeze wages and boost rents.

Calls to reglobalize as quickly as possible do not, UNCTAD argues, offer a desirable route out of this global recession. What the world needs now is a better recovery than the one that followed the last global crisis.

The report focuses, in particular, on the emerging threat of economic fissuring and the resulting income polarization. In a reversal of successful development dynamics, advanced sectors can shed jobs and resources that are absorbed by backward sectors.

Without state commitment to full employment and social protection, flagging demand enables companies in high-productivity/high-wage sectors to restrict market entry and expel workers, who are forced to take jobs in low-productivity/low-wage sectors.

This perverse form of structural change undermines wage growth, setting off a vicious cycle of higher inequality, lower productivity and weaker demand. The result are two-speed economies where advanced sectors contract and backward sectors expand.

The report uses available data – on China and the United States – to illustrate how, under different policy choices, a dual economy can reduce or increase polarization, highlighting a critical feature for a better recovery from the COVID-19 recession.

Building back fairer

The policy cornerstone of a better recovery is income redistribution, which can be achieved by putting full employment and real wage growth at the centre of both macroeconomic and sectoral policies.

While this is already the case in some developed and developing economies, fiscal austerity continues to repress aggregate demand in many countries while the limits of monetary policy as an expansionary instrument have become evident after a decade of record credit creation.

The report argues that public work programmes have a fundamental role to play to secure household incomes while improving ailing infrastructures and public services. Cash transfers such as universal basic income are also important to sustain demand and reduce inequality, especially in developing countries.

But while full employment should be a target of public policy, it is not sufficient to reduce inequality in developed or developing countries. Countries can experience fast job creation, weak growth of demand and sluggish productivity.

To reverse these trends, governments should liberate industrial policy from its constraints in order to expand employment in high-productivity activities and make sure that investment in strategic sectors, including those instrumental to the green transition, takes place at necessary level.

Related, trade policy must be used to favour this effort, encouraging competition at the higher end of the productivity ladder rather than serve as a weapon aimed at labour’s bargaining power.

Public investment critical

Complementing industrial and trade policies, states should return to public investment, a major source of infrastructure spending in most countries. Such investment is particularly important in developing countries, for higher value-added activities to flourish.

It is precisely by limiting public investment that fiscal austerity has hampered structural transformation and sometimes led to its reversal.

In all countries the rules of the economy need to ensure that workers gain a fairer share of value added, the report says. This can be tackled head-on through labour market regulation that supports employees’ compensation.

Raising minimum wages, strengthening collective bargaining institutions and increasing employers’ social security contributions are obvious instruments.

While such measures will need to be tailored to national circumstances, increases in the labour income share can drive up GDP growth by supporting household spending and, indirectly, business investment.

But this will not happen unless better multilateral governance promotes and coordinates a global programme of redistribution and recovery.

Raise wages

Employment and real wages will have to rise significantly to correct the distributional imbalances that have built up under hyperglobalization, but building more inclusive economies post-COVID-19 will also require directly tackling various forms of discrimination, including by race and gender, that continue to segment societies and have a detrimental impact on future development prospects.

Combating workplace stereotypes and otherwise fostering and facilitating access to core sector employment, especially through social infrastructure investments that better enable women to combine paid work and their responsibilities for care, will need to be directly addressed.

Given the employment challenges post-COVID-19, part of gender inclusion for growth and development must be about transforming paid care work into decent work with the wage levels, benefits and security typically associated with industrial jobs in the core sector of the labour market.

More generally, proactive social policy must go beyond offering safety nets or floors designed to pick up (or stop from falling) those pushed behind.

Early data on the unequal health impact of the COVID-19 pandemic adds to existing evidence suggesting that only universal social protection, as opposed to targeted policies, is effective in reducing inequalities.

It can also accelerate and help manage structural transformation, helping to foster technological upgrading and productivity gains, underscoring the interdependence between an economy’s income distribution and its growth performance.

The policies necessary to generate a recovery and make sure it leads to sustainable growth and development are the components of what UNCTAD has been calling a “Global Green New Deal”.

As a policy programme to revive and rebalance the global economy, this strategy would also help establish economic security and generate overall resilience in the face of future shocks.