By Rachid Bouhia, Economist, UNCTAD, and Emily Wilkinson, Researcher, ODI

An empty street in Kingston, Jamaica. / © Anne Fritzenwanker

Prior to the COVID-19 crisis, many small island developing states (SIDS) were already showing signs of increased debt distress – where debt servicing burdens, current account deficits and elevated levels of public debt viciously feed off each other.

The economic fallout from the pandemic is expected to aggravate these hardships, and a wave of sovereign defaults is now looming.

Large-scale borrowing from public and private foreign creditors, particularly after disasters, has given SIDS a diverse set of refinancing options, but this has come with greater exposure to the vagaries of international financial markets, including sudden changes in exchange and interest rates.

In the lead-up to the 26th UN climate change conference (COP26) in November, governments need to focus attention on “fiscal space and debt sustainability” in SIDS, alongside climate finance commitments.

Clear plans are needed to resolve the debt crisis in the short term and debt sustainability over the longer term – so SIDS reduce their vulnerability to climate change and other shocks.

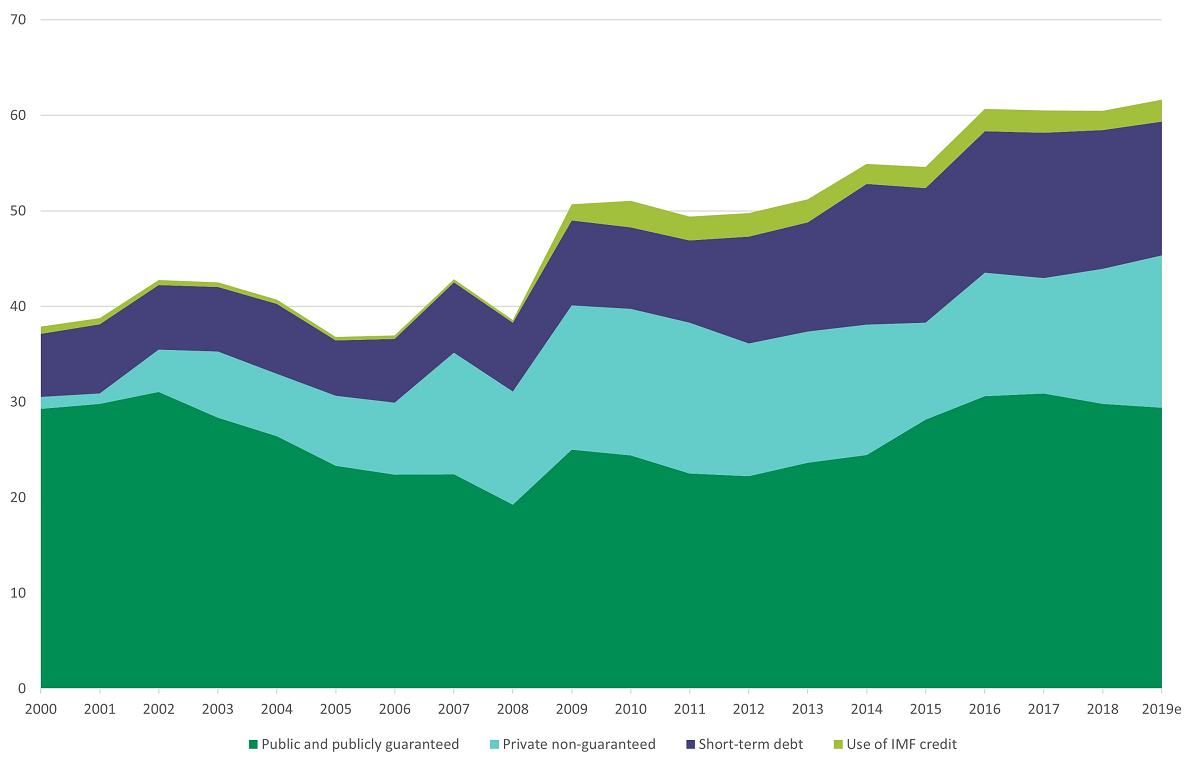

SIDS’ external indebtedness is considerably higher than that of other developing countries. Between 2000 and 2019, the external debt of SIDS rose by 24 percentage points (of GDP), while in developing countries debt fell by 6.2 points on aggregate.

By 2019, external debt accounted for 62% of GDP on average in SIDS (Figure 1), compared with 29% for all developing countries and economies in transition.

Most of the increase occurred in the aftermath of the 2008 global financial crisis, and accelerated in 2013 - the year of the so-called “Taper tantrum”, when US bond yields surged after the Federal Reserve announced a monetary policy normalization (triggering capital outflows from SIDS for higher returns, a currency depreciation and spike in external debt relative to GDP), followed by a series of external shocks, all of which put debt positions under further strain.

Figure 1: External debt (% GDP) in SIDS by main components (2000-2019)

Note: 2019 data is estimated.

Why debt distress is occurring in SIDS

SIDS’ economies suffer from low economic diversification, disproportionate impacts from climate extremes and disasters, and are naturally exposed to public debt distress.

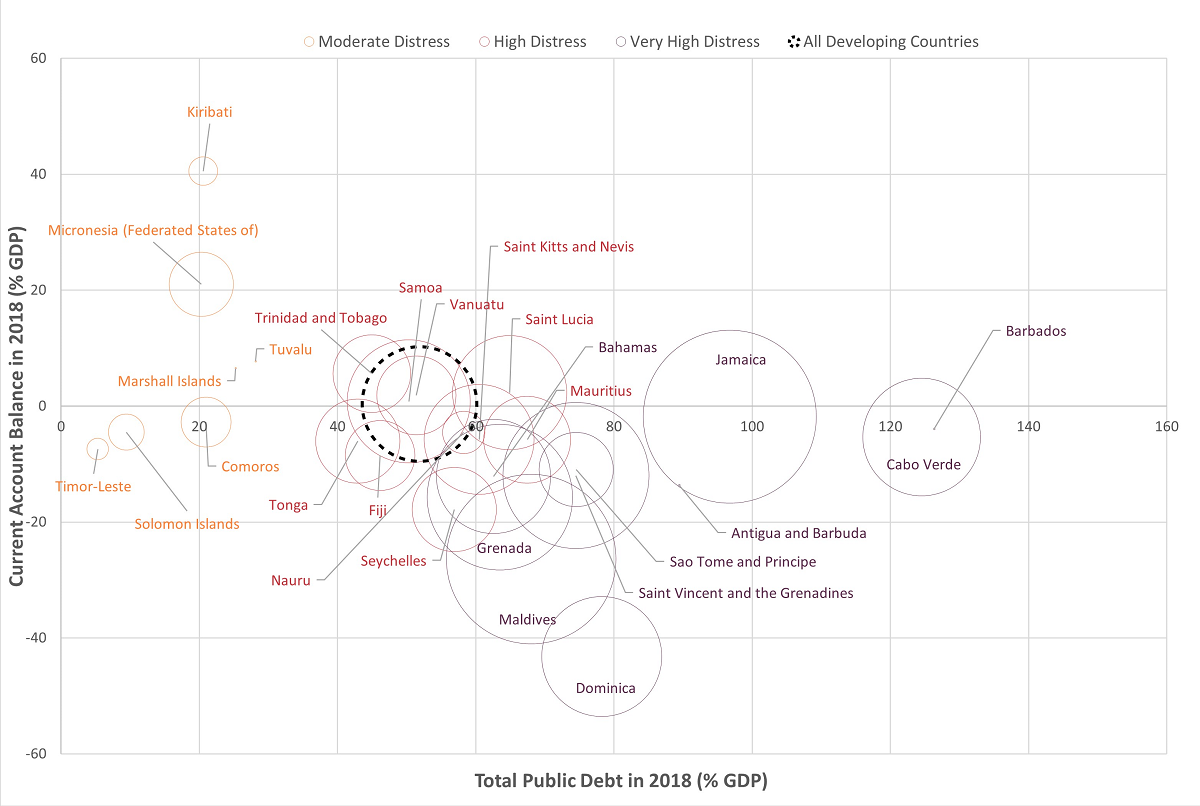

To understand the severity of debt distress, it is useful to look at the ratio of public debt service to government revenues, in relation to total public debt stocks – both external and domestic – and current account deficit.

When these three indicators are simultaneously high, the country is likely to experience debt distress. This means that the country dedicates a huge amount of its public revenues to debt repayments, rather than infrastructure or public services, and as public debt piles up there is very little room to mobilize finance from trade to cope with it.

Figure 2 shows these patterns for SIDS. In Dominica, for example, total public debt is high (78% of GDP); the current account deficit is high (43% of GDP), and the debt service rate is high (10% of government revenues).

Overall, SIDS have higher debt distress than other developing countries, but among SIDS there is a high degree of heterogeneity.

Barbados (which restructured its public debt for the first time in 2018 and 2019), Cabo Verde, Jamaica, Antigua and Barbuda, Dominica, Sao Tome and Principe, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Maldives, Grenada and Bahamas all have particularly high levels.

Figure 2: Levels of debt distress in SIDS

Note: The size of the bubble is the size of the debt service in relation to government revenues (from 0.34% for Timor-Leste to 21.55% for Jamaica). Debt service data is not available for Antigua and Barbuda, Barbados, Marshall Islands and Tuvalu. The classification into the three groups of Debt Distress was made ex-post, in light of the position of the countries in the three dimensions of the graph.

The COVID-19 crisis will severely aggravate the debt positions of these countries, putting them at great risk of defaulting. All except Antigua and Barbuda have benefited from the IMF’s COVID-19 Financial Assistance and Debt Service Relief since March 2020. Only five so far (Grenada, Cabo Verde, Dominica, Maldives and Sao Tome and Principe), have been eligible for the G20 COVID-19 Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI).

What SIDS need now

An agenda for a bold set of actions to jointly tackle the debt and climate crises in vulnerable islands is needed ahead of COP26. This fits with the commitment set by the Paris Agreement for developed countries to provide financial resources to assist developing countries in meeting their climate goals.

To date, this assistance has focused principally on climate finance. Given the impending debt crisis in some of the world’s most climate vulnerable countries, this assistance should also focus on debt relief and debt sustainability.

Specific support is needed in two areas:

- Allowing SIDS some “breathing space”. Given the looming debt crisis, more comprehensive measures are needed – and fast. In particular, an extension of the G20 DSSI eligibility criteria – so that those SIDS with relatively high per capita income levels, which are not currently eligible, can also benefit from ‘debt standstills’. The DSSI also needs to cover all creditors – bilateral, private and multilateral. Given the alarming levels of debt distress in SIDS, it is in the interest of private creditors to join temporary suspension programmes of debt repayments today, to allow time for economic recovery and avert huge financial losses in the future (should the country default or require debt restructuring).

- Re-assessment of the long-term debt sustainability of SIDS. Debt repayment needs to be compatible with restoring and maintaining sustainable and inclusive growth post COVID-19, as well as balanced fiscal and trade trajectories. SIDS need to be able to invest to build the resilience of their economies to climate change and other external shocks, otherwise, debt sustainability is incompatible with climate change commitments.

This article was first published as a blog on ODI’s website.