By Henrique Pacini, Economic Affairs Officer, UNCTAD, and Tze Ni Yeoh, Consultant, World Bank

In 2019, the world traded 550 tons of "waste" worth $315 billion. / © Kalyakan

China’s decision to ban imports of most scrap plastics and other waste materials in 2018 sent shockwaves across the globe.

The Asian giant had imported about 45% of all internationally traded plastic waste since 1992, so the new policy diverted a significant stream of plastic scrap to other countries.

It also raised important questions on how we trade waste, which carries environmental risks related to pollutants and can harm developing economies by dumping cheap, imported second-hand goods in their markets.

550 million tons of used materials traded

In 2019, countries traded 550 million tons of used materials – such as scrap plastics, metals, electronics, paper and second-hand clothes – worth $315 billion.

Since the vision of a global circular economy hinges on turning waste into resources, China’s decision highlights the urgent need to better understand and monitor this trade.

By reducing primary production, secondary materials (recyclable waste) offer immense economic and environmental benefits beyond cutting water consumption and CO2 emissions.

Assessments by the Ellen MacArthur Foundation in collaboration with UNCTAD found that circular economy principles could save China alone $10.3 trillion by 2040.

The world needs a vibrant trade in secondary materials. The question is: How can it be done in a way that better protects people and the planet?

The nature of trade flows – lessons from scrap plastic

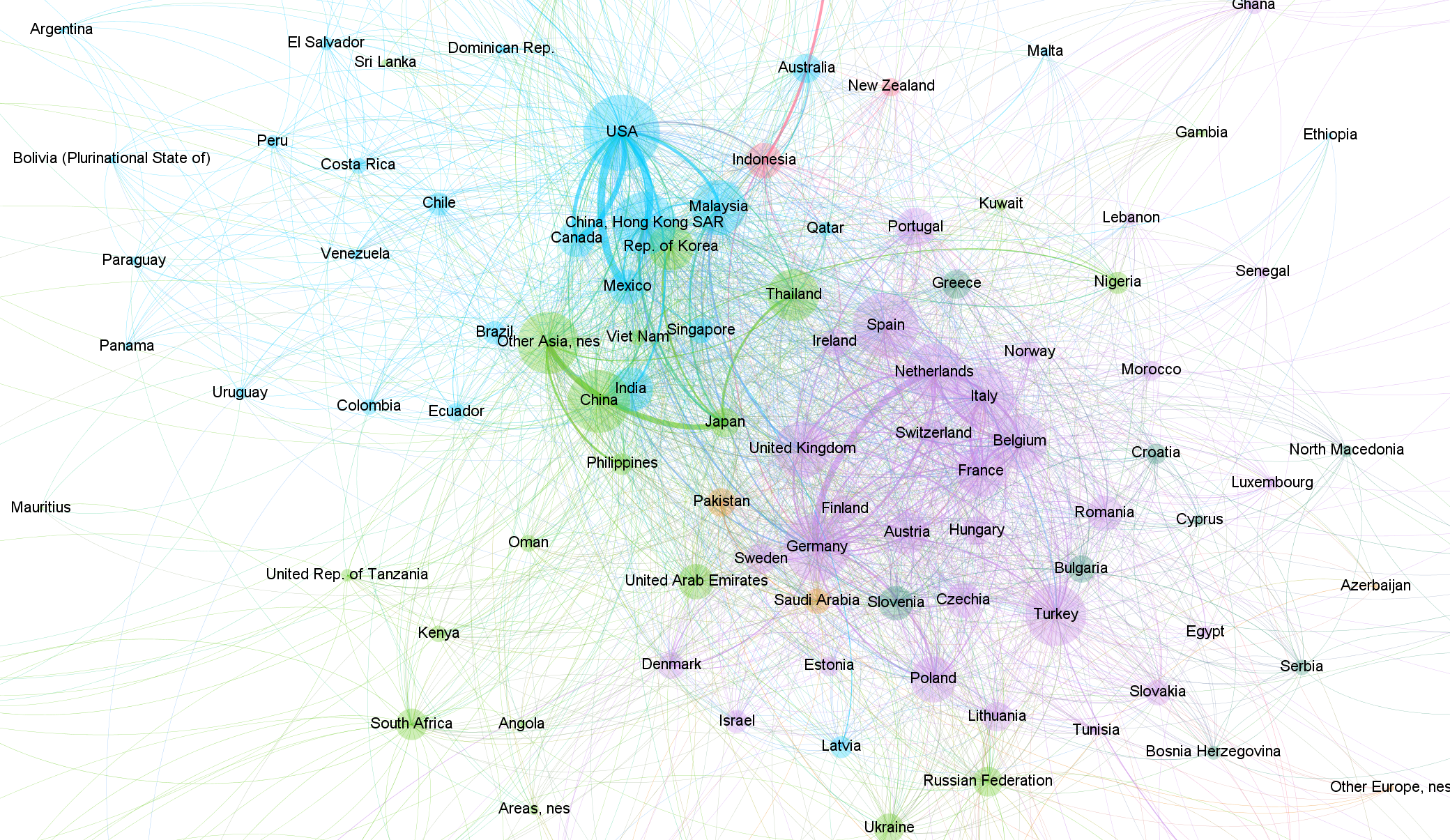

A network analysis of trade data after China’s ban provides important insight into the complex relationships in the trade of plastic waste.

1. Scrap flows towards weaker regulations. When a country restricts the imports of plastic waste, the trade flows tend to be redirected towards poorer countries with weaker regulations, harming the environment. For example, since China’s ban, the imports of secondary material into developing countries has increased significantly. As an example, plastic scrap shipments towards Malaysia tripled between 2016 and 2018, reaching 870,000 tons after China’s restrictions.

But scrap materials do not flow from more developed to less developed countries in a linear way. For example, there are stronger flows of recycled ethylene – a form of plastic widely used for bottles, synthetic fabrics and food packaging – from Mexico to the United States than the other way around.

2. Regional characteristics matter. Research shows that trade clusters for a specific secondary material can be due to various reasons, such as commercial routes, reverse logistics, geographic proximity or trade agreements. Therefore, in addition to global, multilateral plastics governance, it is important to consider regional characteristics and regulations for the “scrap trade”.

3. Low tariffs hinder environmental policy. Imports of mixed plastics are subject to the lowest tariffs, averaging only 5.4%, compared with more than 6% for all other types of scrap plastics. This is contrary to environmental policy objectives since mixed plastics are harder and more costly to recycle and thus worse for the environment. Mixed plastics account for more than 50% of all recycled plastics traded across borders, in terms of both value and weight.

4. Illicit trade grows in the shadows of waste. There is evidence of a sizeable “shadow economy” in the trade of plastics scrap. One article finds large price discrepancies between trade partners’ declared exports and imports. On average, exporters declare values 18.47% higher than importers, which is contrary to the discrepancy typically reported in international trade. The magnitude of illicit trade flows in waste is huge, according to the World Customs Organization (WCO). Its largest seizure so far is 180,000 tons of smelting slag shipped illegally from Spain. But WCO operations are just a snapshot. More data is needed.

Trade of scrap plastic, 2018

Collaboration needed to improve governance

Effective collaboration between various international groups is needed to improve the governance of secondary materials and promote a responsible, SDGs-oriented circular economy.

Examples include the Basel convention amendment, which is helping improve plastic trade, as well as a recently created working group of the World Trade Organization (WTO) to coordinate global action on plastics.

UNCTAD has been supporting WTO members concerned with oceans plastics pollution, and providing technical assistance to countries in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia through a sustainable manufacturing programme (SMEP) supported by the United Kingdom. UNCTAD is also leading research on substitutes to single-use plastics in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia.

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and World Bank are also mainstreaming such discussions, taking a systems approach that considers production and disposal.

The years 2021 and 2022 are important for global materials stewardship, to be discussed at international gatherings such as the BRS conventions, the 5th session of the United Nations Environment Assembly (UNEA-5) and the UN Environment Programme’s International Conference for Chemicals Management (ICCM5).

The private sector and civil society are also responding with initiatives such as the Alliance to End Plastic Waste and the Platform for Accelerating the Circular Economy (PACE). And governments are exploring mechanisms such as extended producer responsibility schemes to promote the circular economy.

Beyond plastics

Improving the governance of trade in secondary materials goes beyond plastics. In December 2020, the WTO formed a working group on trade and environmental sustainability that is supported by over 50 members.

It seeks to strengthen discussions around topics such as climate change, the circular economy and biodiversity protection in the run-up to the 12th WTO ministerial meeting scheduled for late 2021.

Information sources such as the Chatham House Portal open possibilities for research on how to extend the lessons learned on plastics to other materials.

While there has been significant progress in the governance of scrap plastics at a high-level, its success ultimately depends on enforcement. Hence stakeholders from global to local levels must hold each other accountable and work cohesively to translate plans into action.

An earlier version of this article was first published on Chatham House’s Circulareconomy.earth

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of their organizations.