UNCTAD and UN regional commissions are piloting new methods for tallying the cross-border movement of money that is illicit in origin, transfer or use.

African currency notes. © vkilikov

As countries across the globe try to alleviate the economic and social pain caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, billions of dollars are leaking across their borders in the form of illicit financial flows (IFFs).

This massive stream of money moved illegally from developing countries erodes their already limited financial resources to invest in the public services needed to recover sustainably, such as health and education.

In Africa, for example, UNCTAD estimates that some countries with high IFFs spend on average 25% less on health and 58% less on education compared with countries with low IFFs.

Why collaboration matters

A lack of reliable data limits states’ capacities to curb the massive stream of money moved illicitly from one country to another through activities such as illegal and illicit tax and commercial practices like trade misinvoicing and profit shifting.

“The production of IFF estimates is very challenging,” said Anu Peltola, who heads UNCTAD’s statistics branch. “As an illicit phenomenon, IFFs are not easy to track or measure.”

“The urgent task of tackling IFFs,” she said, “is hindered by the fact that the information needed to measure the illicit flows of money cannot be captured by a single data source. This calls for collaboration of national authorities within and across borders.”

New guidelines and a pilot programme

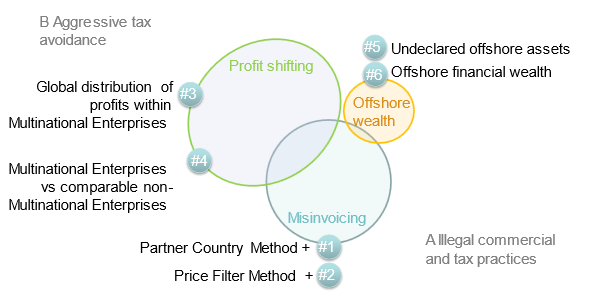

UNCTAD published in May 2021 new methodological guidelines for measuring tax and commercial IFFs that occur through trade misinvoicing by entities, aggressive tax avoidance or profit shifting by multinational enterprises, and the transfer of wealth carried out by individuals to evade taxes.

“Probably the trickiest part of the commercial side conceptually is to understand the difference between illegal and illicit,” UNCTAD statistician Bojan Nastav said.

“The clearly illegal part, while still not easy to measure, is tax evasion. Tax avoidance on the other hand is a greyer area. It's not illegal but can be highly detrimental in large volumes,” he said.

UNCTAD has since teamed up with the UN regional commissions for Africa (ECA) and Asia (ESCAP) to pilot the guidelines in more than a dozen countries in the two regions.

The African countries carrying out pilot studies include Angola, Benin, Burkina Faso, Egypt, Gabon, Ghana, Namibia, Nigeria, Mozambique, Senegal, South Africa and Zambia. The Asian ones studying tax and trade-related IFFs are Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan.

An interregional workshop

In December 2021, UNCTAD and its partners organized a one-week training workshop for members of the technical working groups of the pilot countries.

Participants included statisticians and officials from national agencies such as national statistical offices, central banks, tax and revenue authorities, customs, financial intelligence centres and ministries of finance and justice.

The training aimed to improve their understanding of the guidelines and the six suggested statistical methods (see the figure below).

Suggested statistical methods for measuring tax and commercial illicit financial flows

Source: UNCTAD's statistics branch

“Understanding the low tax-GDP ratio in Ghana requires a comprehensive appreciation of plausible tax manipulation, of which aggressive tax avoidance and commercial illicit financial flows cannot be sidestepped,” said Samuel Kobina Annim, head of the Ghana Statistical Service.

“This underscores the interest of Ghana Statistical Service to measure IFFs as a part of its regular dispensation,” he added.

Ms. Peltola said each country can select the methods best suited for it since the guidelines propose two for each type of commercial and tax IFFs. “The countries will also first focus on the IFFs that they deem most relevant and feasible to measure.”

In addition to providing in-depth training on the statistical methodologies, the workshop also provided participants with case studies and allowed national authorities to share their experiences and discuss new challenges revealed by pilot studies.

The interregional nature of the workshop helped to strengthen international collaboration between agencies – a prerequisite for effectively addressing IFFs.

Towards globally agreed methodologies

Ms. Peltola said the pilot programme, which will run until June 2022, funded by the UN Development Account, is key not only to strengthening countries’ capacities to measure IFFs but also to testing the feasibility of the recommended methodologies in practice.

The results of the pilot phase will help develop a globally agreed methodology to measure IFFs and the related Sustainable Development Goal indicator 16.4.1, for which UNCTAD and the UN Office on Drugs and Crime are the custodians.

The two UN bodies have established an international task force to develop a conceptual framework to measure IFFs that will include guidelines for collecting statistics from illegal markets, corruption and exploitation-type activities, such as the trafficking of people, kidnapping and theft.

The information gathered will not only provide clarity on IFFs – their types, sources and destinations – but also help improve the quality of key macroeconomic statistics, such as GDP, which can also be affected by large illicit financial flows.

“Objective and reliable data and statistics on IFFs, compiled and reported in a coordinated way by the national statistical office in each country and in full adherence to the Fundamental Principles of Official Statistics, are key to curbing IFFs,” Mr. Nastav said.

“This is what our joint work with countries is aiming to achieve.”