The UN's trade and development body outlines a set of recommendations to realign the global debt architecture with developing countries’ needs.

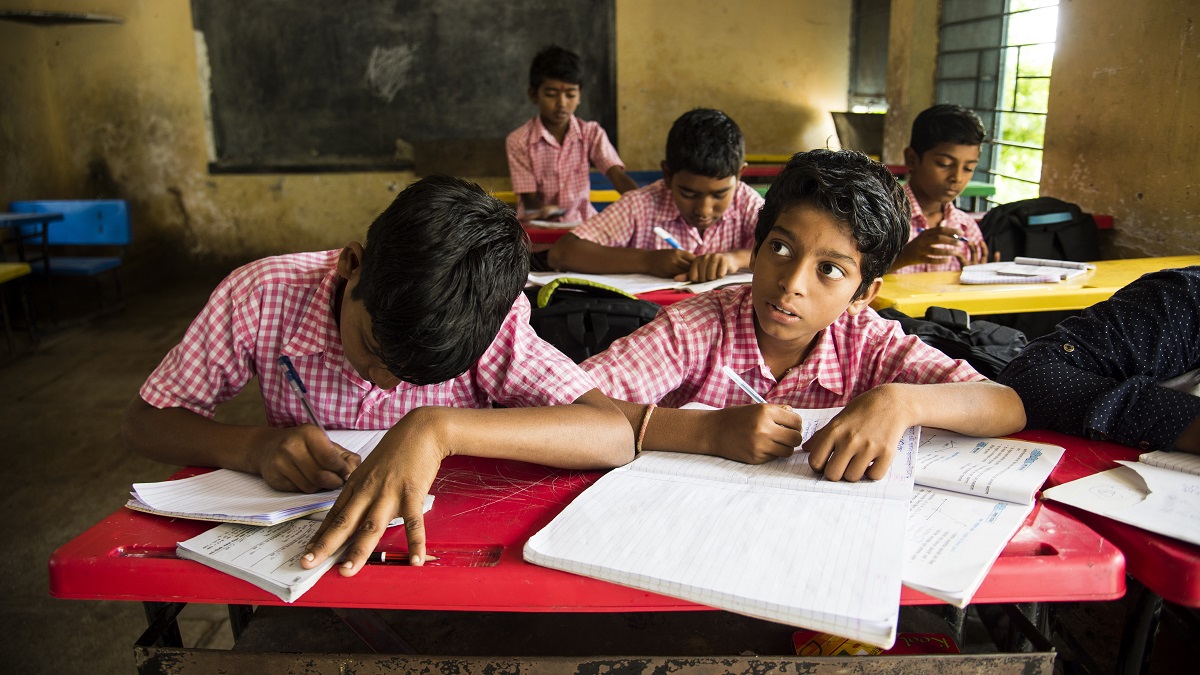

© Shutterstock/CRS PHOTO | A classroom in rural India. About 3.3 billion people live in countries that spend more money paying interest on their debts than on education or health.

UNCTAD has called for urgent reforms to the global debt architecture to avert a widespread debt crisis among developing countries.

In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, developing countries’ external debt – funds borrowed in foreign currency – increased by 15.7% to $11.4 trillion by the end of 2022. The mounting debt levels are further complicated by the diversity of lenders and financial instruments.

Equally alarming is the surge in debt servicing costs. Low-income and lower-middle-income countries – also referred to as frontier markets – that borrowed when interest rates were low and investors keen are now spending around 23% and 13% of their export revenues, respectively, to repay their external debt.

“To put this in perspective, after World War II, the share of export revenue going into debt servicing for Germany was capped at 5% to aid West Germany’s recovery,” says Anastasia Nesvetailova, head of UNCTAD’s macroeconomic and development policies branch.

The rising debt costs are draining vital public resources needed for development. About 3.3 billion people – almost half of humanity – now live in countries that spend more money paying interest on their debts than on education or health. The UN’s “A World of Debt Dashboard” provides data and in-depth insight on key public debt and development spending indicators for 188 countries.

“This situation is clearly unsustainable,” Ms. Nesvetailova says. “While a systemic debt crisis, in which a growing number of developing countries move from distress to default, looms on the horizon, a development crisis is already underway.”

A development-centred approach to debt is needed

Ms. Nesvetailova underscores that the mounting debt crisis stems not only from the wave of debt after the Global Financial Crisis of 2008, the cascading crises since the pandemic and the aggressive monetary tightening in developed countries. She points out that the main roots lie in the structural flaws of the global sovereign debt architecture, “which offers inadequate and delayed support to countries in debt distress.”

UNCTAD’s latest Trade and Development Report unpacks the current inequalities, inflexibilities and problems of the global sovereign debt architecture, outlining a strategy to address them.

“A development-centred approach to debt is needed,” Ms. Nesvetailova says, highlighting overlooked factors contributing to unsustainable sovereign debt, such as climate change.

The report advocates for a thorough re-evaluation of these factors, which encompass demographics, public health, global economic shifts, rising interest rates, geopolitical realignments, political instability, as well as the implications of sovereign debt on industrial policies in debtor states.

It proposes a five-stage life cycle for sovereign debt as a conceptual framework to analyse and improve the global debt architecture. The stages include incurring debt, issuing debt instruments, such as bonds and loans, managing debt, tracking debt sustainability and, if necessary, restructuring or renegotiating the terms of debt.

“We’re urging new creative thinking in all stages of the debt cycle, as well as new approaches to bridge the persistent divide between statutory and contractual solutions,” says Penelope Hawkins, head of UNCTAD’s debt and development finance branch.

Recommendations and policy actions

The UNCTAD report outlines a comprehensive set of recommendations to recalibrate the global debt architecture in line with developing countries’ needs.

A key recommendation is to boost concessional loans – characterized by lower interest rates and longer repayment terms – and grants. This could be done by increasing the base capital of multilateral and regional banks to expand their lending capacity.

Another way to raise concessional finance involves issuing special drawing rights (SDRs), a type of international currency the IMF created for member countries to boost their monetary reserves by exchanging them for official currencies as needed.

Also important is more transparency in financing terms and conditions. The report says that reducing resource and information asymmetry between borrowers and lenders, coupled with legislative measures in lender countries, can discourage predatory lending practices.

“But transparency goes beyond data disclosure,” Ms. Hawkins says. “It signifies a commitment to constructing a global financial architecture that is fair and accountable to all.”

Further recommendations include expanding developing countries’ access to foreign currencies through central bank swaps and enhancing their resilience during external crises through standstill rules on debtors’ obligations, such as climate-resilient debt clauses. This would allow a halt in debt repayments, providing some breathing space for crisis management.

“Greater use of contingent clauses in contracts is necessary for countries experiencing climate and other external shocks,” Ms. Hawkins says.

The report also says that the global debt architecture requires well-developed rules for automatic restructurings and a better global financial safety net. Finally, it underscores the urgent need to begin work on establishing a global debt authority to coordinate and guide sovereign debt restructurings.

“The time to act is now,” Ms. Hawkins says. “The costs of inaction are too high.”