Written by Paul Akiwumi and Giovanni Valensisi, Division for Africa and Least Developed Countries, UNCTAD

As the number of COVID-19 cases continues to rise in Africa and Southern Asia, and the global economy enters a synchronized recession unseen since the Second World War, the world’s poorest countries brace for yet another shock that threatens to deepen global inequalities and exacerbate an already challenging situation.

Public health and socio-economic concerns are deeply intertwined all over the world, but all the more so in contexts like the least developed countries (LDCs).

Indeed, even though two-thirds of people in LDCs live in rural areas, many of them reside in overcrowded urban settlements lacking basic services. They can hardly cope with strict social distancing, as well as broader economic shocks that directly affect their income.

Even prior to the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic, respectable gross domestic product (GDP) growth rates in the 47 LDCs were only weakly translating into inclusive social outcomes.

The decline in poverty headcount ratios had markedly decelerated in the aftermath of the 2009 global financial crisis.

Over the last decade, it has been so sluggish that the number of people living in extreme poverty (i.e. below $1.90/day) in the LDCs has increased from 340 million people in 2010 to an estimated 349 million in 2018. This was largely due to the situation in African LDCs.

Reversing progress

The interplay between the COVID-19 outbreak, the contraction in demand – globally and even more so in some of LDCs’ major trading markets – and the free-fall of international commodity prices will likely reverse the limited progress that has been made in poverty reduction.

This will steer us even further away from achieving the first United Nations Sustainable Development Goal of ending poverty in all its forms everywhere.

To provide a preliminary appraisal of the impact of COVID-19 on LDC poverty levels, UNCTAD has examined the International Monetary Fund’s growth forecasts in GDP per capita (in constant 2011 international dollars) and looked at the effects, stemming from its downward revision following the outbreak of the pandemic.

This allows the direct comparison of poverty estimates consistent with the IMF’s reassessment of growth forecasts between October 2019 and April 2020.

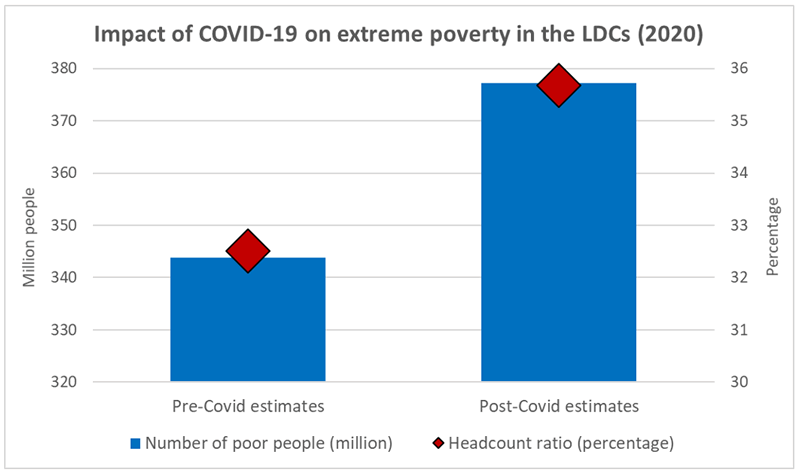

The results of this UNCTAD research are highlighted in Figure 1: the worsening economic outlook following the emergence of COVID-19 entails an increase of over three percentage points in LDC poverty headcount, with more than 33 million additional people living in extreme poverty.

While this exercise is fraught with uncertainties, there are good reasons to believe that these figures are – if anything – a conservative estimate.

First, simulations are only run until the end of 2020, since future outcomes will largely depend on policy responses that are still unfolding; hence they neglect by construction the impact of the crisis beyond 2020.

Crisis will deepen beyond this year

Yet, there are considerable risks that the crisis may deepen or even linger on beyond the end of 2020, especially if it triggers balance of payment tensions and/or debt crises in the developing world.

Second, the methodology employed assumes that the shock leaves unchanged the distribution of income; however, it is reasonable to expect that some of the poorer segments of the population will be hardest hit.

For example, with 70% of the LDC labor force being self-employed, strict social distancing is likely to exert a disproportionate effect on informal workers and micro, small and medium enterprises, which have meagre resources to weather the confinement without disruptions.

Moreover, the negative impact of the pandemic may be felt through other transmission channels than the pure income dimension and even create adverse long-term effects on households’ living standards.

This could be the case, if the suspension of the school year permanently lowers educational quality, or if poor households are forced to take their kids out of school to cope with lower income.

Similar events might lower households’ future income prospects, potentially turning a temporary shock (so-called “transient poverty”) into a longer-term phenomenon.

It is clear at this stage that the fallout of the pandemic risks eroding much of the socio-economic gains recorded since the adoption of the Istanbul Programme of Action, in terms of reducing extreme poverty in the LDCs.

Four-pronged approach needed

Mitigating this adverse effect hinges on a four-pronged approach.

First, the international community must support LDC governments in mobilizing adequate resources to allow their health systems to cope with the emergency, while also assisting vulnerable segments of the population.

This calls for the provision of emergency financial resources – preferably on a grant basis – and of technical support, as well as secure access to critical medical supplies.

Second, containing the social costs of the pandemic requires averting balance of payment crises that would further strain LDC economies, and risk triggering food shortages as most countries in the category are net food importers.

Critical to this effort, given the current fall in commodity prices, the structural nature of LDC current account deficits and the recent build-up in their external debt stocks, is the provision of adequate international liquidity, a moratorium on debt servicing and in some cases renewed debt relief to preserve much-needed foreign exchange.

Thirdly, it is crucial to avoid major disruptions to domestic and regional food and agricultural value chains.

With the immediate socio-economic effects of the pandemic mainly affecting the urban population, the viability of agriculture is fundamental to preserve livelihoods in rural areas, contain price spikes for staple foods and limit food import bills when foreign exchange is scarce.

Fourthly, in the longer-term, international cooperation must be revamped to:

-

Adopt concerted expansionary policies to blunt the impact of the crisis and revitalize the global economy.

-

Redouble investments in sustainable development, thus spurring the transition towards a low-carbon economy.

-

Keep critical value chains (such as food and medical equipment) viable, thus avoiding the painful mistakes that followed the 2007-2008 food crisis; and finally.

-

Foster productive capacity development and structural transformation in LDCs as key elements of a policy package to build resilience and lay a robust foundation for employment creation.