Food insecurity has been a long-standing concern in least developed countries (LDCs), but COVID-19 is exacerbating this problem, derailing progress towards UN Sustainable Development Goal 2, which aims to achieve “zero hunger”.

Date: 1 August 2021

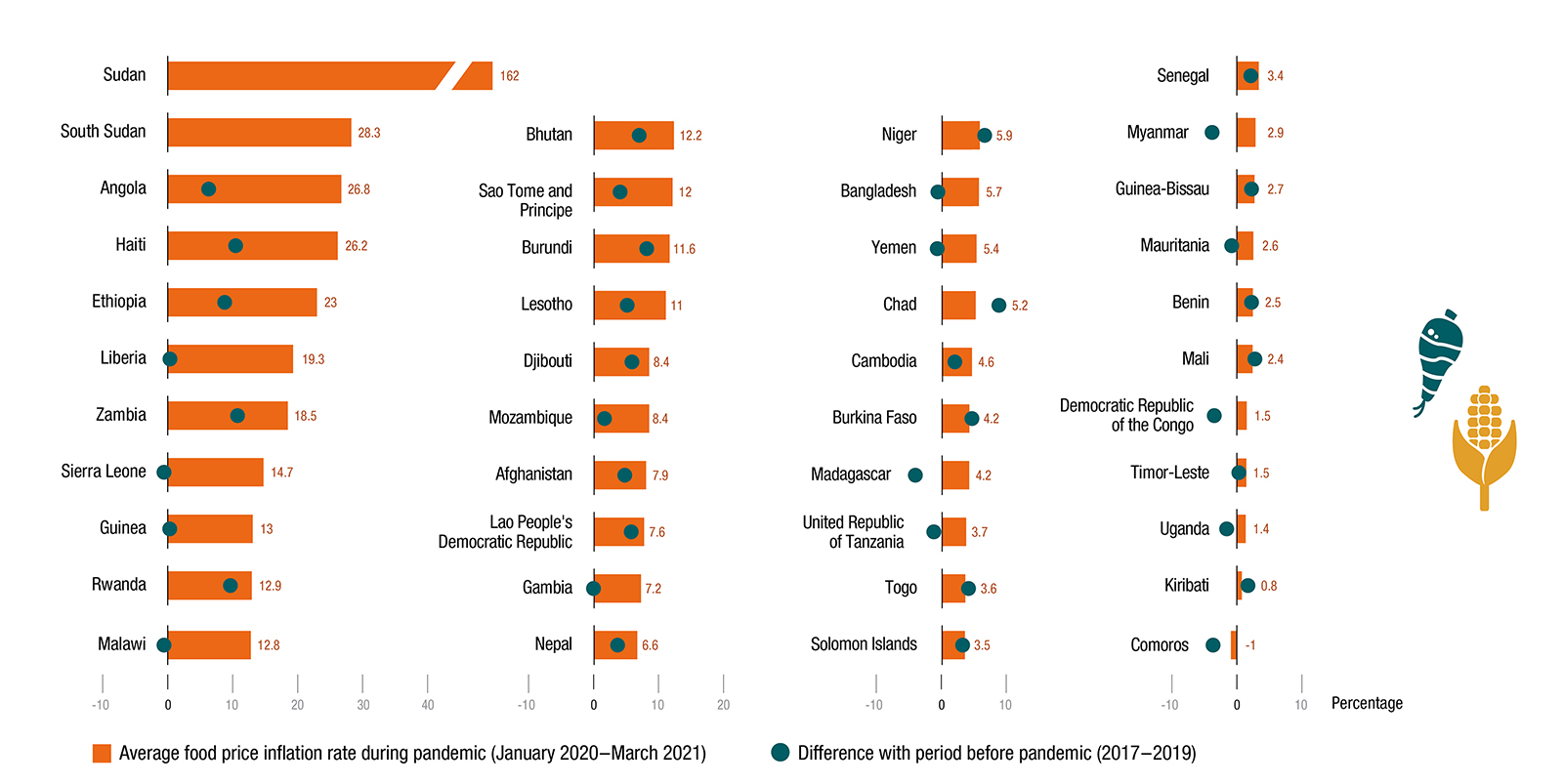

Source: UNCTAD secretariat calculations based on data from FAOSTAT.

Note: Figures are period averages of monthly data. Data points for the difference in inflation rate compared to the pre-pandemic period for two outliers – South Sudan and Sudan – are not displayed to ease readability.

The above chart shows that food price inflation has been on a rapid and accelerating trend in most LDCs, which also face recessions triggered by the fallout of COVID-19.

Between January 2020 and March 2021, the median LDC average food inflation rate was over 6%, with 15 LDCs recording a double-digit inflation rate. In two thirds of the LDCs for which data is available, food price inflation since the outbreak of the pandemic has exceeded the average of the previous three years.

At a time when economic recovery is sluggish and poverty rates are soaring, this significantly lowers food affordability. It also worsens food insecurity, particularly among the most vulnerable and those living in fragile contexts, compounding already existing inequalities in access to sufficient nutritious food.

In addition, globally, the gender gap in terms of food insecurity has grown even larger during the pandemic, with food insecurity being 10% higher among women than men in 2020, compared with 2019.

Need for sustained agricultural development

Stopgap measures such as targeted food vouchers remain critical at this stage, especially in contexts where food insecurity is exacerbated by conflicts and other shocks, such as extreme weather events or pests. But they’re not sufficient.

A long-term strategy to increase the availability of nutritious foods and reduce malnutrition in LDCs hinges on sustained agricultural development and the transformation of rural economies.

Enhancing investments in basic infrastructure (including in transport systems, rural electrification, irrigation and storage facilities, among other aspects), extending access to credit and supporting the adoption of more efficient agricultural practices remain key priorities.

Equally critical is stronger support for research and development and extension services to spur the adoption of improved seed varieties and digital technologies to improve agricultural productivity, resource use efficiency, access to reliable information and support climate resilience, especially among smallholders.

Finally, a more conducive ecosystem that places emphasis on fostering the emergence of rural non-farming activities and rural entrepreneurship remains crucial to income diversification and structural transformation.

Download:

- The Least Developed Countries Report 2020: Productive capacities for the new decade

- The Least Developed Countries Report 2018: Entrepreneurship for structural transformation: Beyond business as usual

- The Least Developed Countries Report 2015: Transforming Rural Economies