Written by Mikael Lind, Wolfgang Lehmacher, Kris Kosmala and Mark Scheerlinck, Article No. 126 [UNCTAD Transport and Trade Facilitation Newsletter N°103 - Third Quarter 2024]

© Shutterstock

Can terminals become the game-changers and healers in international value chains? The global logistics and transport ecosystem is a complex network of connected nodes through which shipments flow seeking their most efficient routes from origins to destinations to satisfy the needs of the shippers. At the nodes terminal operators are handling the containers. The terminal operators’ main goals are the efficient, safe, and secure transit of goods and a maximum return on assets (ROA).

Many have tried to improve the reliability and efficiency of global value chains through higher visibility and better synchronization of the flow of goods. But despite major improvements in ships, vehicles, systems, and equipment, visibility and synchronization remain poor. Containers are regularly delayed and miss their connections. What about taking corrective action at the terminals? What if terminals could help shippers reduce their greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions? Data and the ability to single out individual containers for special handling are the grounds on which such an intervention as part of new terminal operator value propositions can be built.

This article discusses a potential new role of terminals with novel value propositions to stakeholders along the international value chains. The implementation of such innovations requires fundamental changes to the traditional way of working in international transport. As the pressures along the chain have been constantly building up through accelerating disruptions, the shift seems to be worth a deeper reflection.

Terminal operator landscape

The terminal operator landscape is diverse. Every port/terminal has its purpose, scale, customer base, business strategy, etc. The terminal landscape consists of larger and smaller hubs and similarly larger and smaller gateway ports. Shanghai which handles the largest volume in the world is primarily considered a gateway port. Large ports may be burdened by congestion seeking efficiency through seamless coordination and synchronization. Smaller ports may suffer from a lack of volume looking for a competitive edge, e.g., flexible operating models and a broader range of services. Terminal operators set themselves up based on the situation and requirements of their customers, mainly the shipping lines or very large shippers.

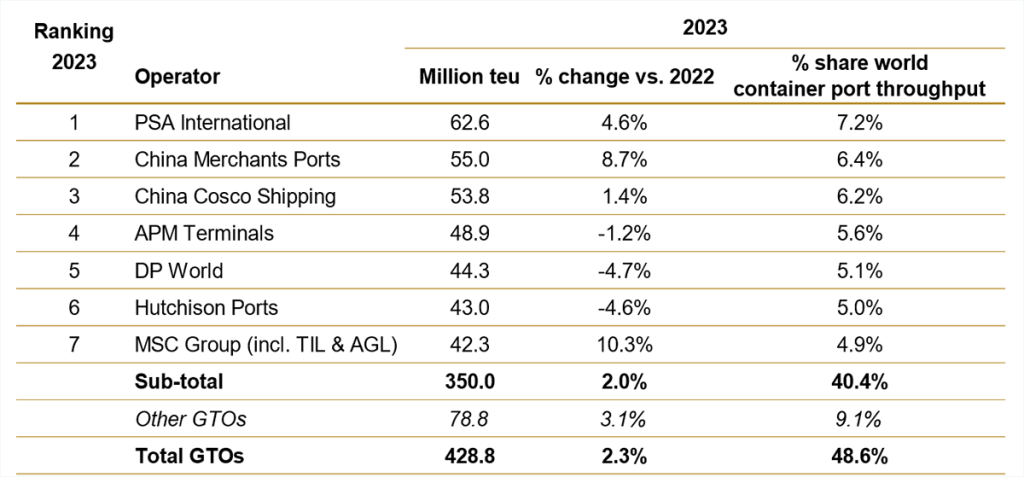

Larger container terminal operators may run 50 to 100 terminals globally. Table 1 lists the seven largest terminal operators ranked on the volume handled in 2023. Usually, terminals operate a mix of larger and smaller ports to offer their customers broader coverage sparing them fragmentation of supply.

Figure 1: Leading global/international terminal operators, equity-adjusted throughput, 2023

Terminals can also be characterized by what they handle, e.g., industrial or consumer goods. Or whether they are export or import terminals. All terminals do kind of both but typically some characteristics are more prominent and enjoy more attention from the terminal operators. As an example, in Sweden, Gävle container terminal which mainly handles exports and industrial goods differs from Norrköping Container terminal which mainly handles imports and consumer goods. These characteristics drive different strategies, behaviors, goals, and interests regarding stakeholder engagement. Export and industrial terminals focus typically more on information about the arrival of containers from the landside and their departures by ship. Import and consumer goods terminals focus on whether a specific container has arrived with a ship and departed by train, truck, or barge. These different perspectives orient strategies and value propositions.

Current terminal practices

The terminal operator aims at handling, loading, and discharging goods as safely, securely, and efficiently as possible to enable fast turnarounds. The more regular the arrivals of ships, the easier the alignment along the chain and the higher the ROA. Schedule reliability is paramount for terminal operators as they generate returns on efficiency through panning certainty. Cargo owners are also interested in fluidity to avoid additional costs, like demurrage penalty fees charged for containers that stay longer than permitted in the yard.

Leading ports integrate with relevant stakeholders, including transport and logistics providers, and warehouse operators. In multi-modal settings, terminal operators serve shipping lines with cargo operations beyond their seaside and inland terminals. Terminal operators have been invited to support synchronized visits through initiatives like the IMO just-in-time arrival concept, which reduces negative impacts on cost and capital deployed and on the environment and climate. Various platforms, like Maritime Emissions Portal (MEP), port optimization software, and Environmental Management Systems (EMS) use different data sources like ship data, AIS data, or port data to help ports, terminals, and cargo owners calculate their emissions, the more accurate the data, the more precise the calculations. Also, sustainability efforts, like green corridor collaborations, energy management, and emissions reduction programs need a beyond-the-gate approach.

Historically, terminals have been owned and operated by governments but over time many governments decided to become pure landlords leaving the operations to private sector actors. Today, some shipping lines operate their terminals, Maersk owns APM Terminals, MSC runs TIL, and China’s COSCO operates COSCO Shipping Ports. In seaports where they do not operate terminals, shipping lines contract agents. Often the same agent represents multiple carriers. The shipping agent helps the crew with documentation and navigating port-specific operations and informs the terminal of the estimated arrival time (ETA). Often, the ETA information flow is broken. The information that flows from captain to carrier, agent, port, and terminal is a source of error, sometimes resulting in ETA differences of multiple days. Add freight forwarders and alliance partners to the mix and more ETAs come into existence. Unreliable ETAs make terminal planning challenging, result in delays of subsequent ships, and distort the scheduling of land transport for container evacuation. The costly complexity of such practices accumulates fast.

In the port, the different port stakeholders can connect to a port community system (PCS), an electronic platform that can be accessed by the community members. The platform is shared in that it is set up, organized, and used by different actors. PCSs display the ETAs received without any checks and verification. Closer collaboration between the different actors in the chain would require an update of current practices and PCSs. Once the vessel is at berth, the PCS stops informing and the terminal information platforms take over. Those are custom-built, as there is no standard for or collaboration toward what a terminal platform should cover. Terminal operators could use initiatives like the Virtual Watch Tower (VWT) for improved disruption and carbon footprint management as a means of standardization, following the TIC 4.0 model, which promotes, defines, and adopts standards for cargo handling in the digital age.

The VWT is a shipper-driven, terminal-centric, distributed, and community-driven virtual watch tower / VWT initiative that has been launched to engage shippers, transport operators, terminal operators, technology providers, and research organizations to improve visibility through primary data sharing for augmented disruption and carbon footprint or greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions management aims at establishing a new quality of supply chain and transport visibility. This could be foundational for closer collaboration between shippers, carriers, and terminal operators and the basis for new services.

Terminal-related pain points

The shippers expect goods to be delivered as originally communicated by the carriers. Cargo owners know that things can change or go wrong, but they require transparency about what happens and updated transport plans, and this, ideally when deviations and updates occur and not much later. This would empower cargo owners to inform their partners and take corrective action if possible and needed. Terminals use their track and trace systems and share information with the carriers via EDI or Web Services. Carriers, including freight forwarders, display data in their portals visible to the shippers, but regularly late, and the date can diverge significantly between different actors. Furthermore, terminals are usually not informed about the details of the cargo owner or consignee. The carriers hold that information. They are the single point of contact for the shipper for container information and they bill the cargo owners for the services related to the container.

What about probing a new collaborative partnership of trust between terminals, carriers, and shippers, a primary data-sharing partnership for enhanced visibility and improved disruption and carbon footprint management?

A comprehensive data offering could move terminals toward the vision of a logistics service center as the basis for supply chain synchronization, improved disruption management through corrective actions at nodes, and more accurate GHG emissions calculations, all enabled by additional and accurate data from the source.

The communication between shippers, terminals, and other actors should not be a one-way street. Terminals plan the yard stacks in preparation for loading and unloading. Usually, the shippers do not inform the terminals of pick-up and drop-off times for their boxes. The stowage plans of the ocean carriers guide the export stacking of containers. Imports are more challenging, and terminals experiment with appointment booking systems which are seen as undue bother and bureaucratic by shippers and transport providers. However, the lack of visibility can cause significant rehandling of containers when the truck arrives for pick-up.

The shipper-driven and terminal-centric VWT initiative can support the efforts as an enabler of primary data sharing, empowering the different actors to provide information back and forth. VWT involves terminal operators, supply chain actors, and technology providers to contribute to the development of the VWT data sharing/volunteering mechanism that can achieve many data-dependent goals along international value chains.

An opportunity for terminal operators

Recently, the reliability of shipping services has suffered due to severe supply chain shocks. Terminals handle units/containers which could allow them to provide container-specific services that course correct in case of deviations from transport plans. Terminals could offer such services provided shippers and carriers augment their visibility. This requires confidence and new forms of collaboration between cargo owners, carriers, and terminal operators. In other words, the relationships between the parties need to be restructured. Certainly, individual business cases are needed to provide answers to questions about investments in new services and the respective returns.

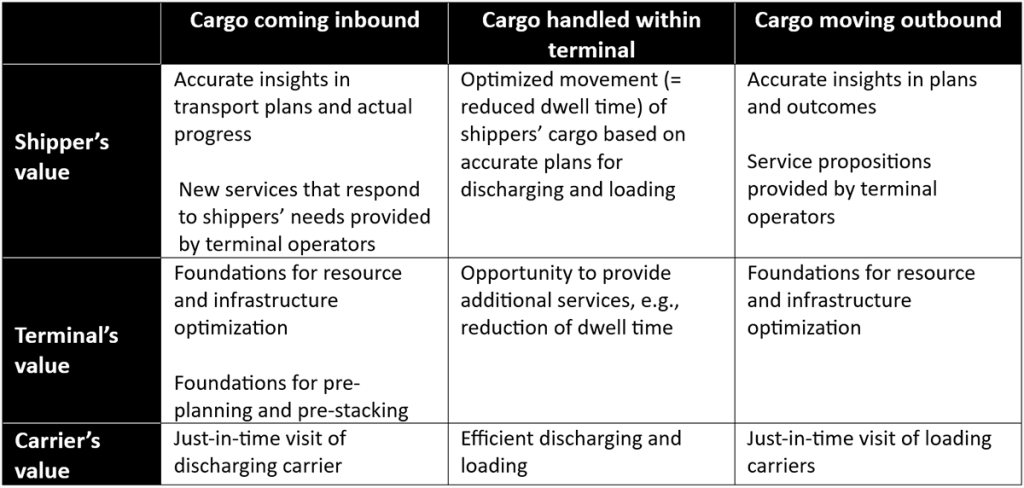

We have outlined some potential value propositions enabled by new terminal operator services by using a nine-field matrix along the dimensions of the type of cargo flows and stakeholder benefits (Table 1).

Table 1: Approach to defining individual value propositions

VWT could be the catalyst of confidence enabling new relationships and providing the place where they are operationalized. VWT offers a fresh approach to primary data-sharing which can be beneficial for all stakeholders. Terminal data is part of the scope of VWT. As VWT is not only a digital solution but also a community of like-minded advocates of data-sharing, new revenue streams and sources of profit might open for all parties as motivation to lift the level of trust and restructure their relationships.

Conclusions – a worthwhile effort

Shippers contract, directly or indirectly, shipping lines for the carriage of their goods. In turn shipping lines contract terminals for the handling of the goods. So, there is no contractual tie between shippers and terminals. However, aligning and exchanging data and information between terminals and shippers could greatly improve the flow of cargo and the throughput at the terminals. This is where VWT is expected to provide value through facilitating primary data exchange. VWT provides a win-win-win solution for shippers, carriers, and terminal operators.

This article calls for probing an extension of the terminal operator role through new value propositions. Certainly, this requires a shift in attitudes, relationships, transparency, and practices along the chain.

This radical rethink and redesign could start with a contract review to understand what arrangements would need adjustments. The transformation can only be achieved through a community ready to establish a new level of confidence and visibility, as the foundation for novel services in international value chain networks. VWT is well-placed to be a catalyst for such an innovative shift. The driver of such a transformation is the additional capital created.

Contact the authors:

Mikael Lind | Research Institutes of Sweden (RISE) & Chalmers University of Technology | [email protected]

Wolfgang Lehmacher | Anchor Group & Topan AG | [email protected]

Kris Kosmala |YILPORT Holding Inc. |[email protected]

Mark Scheerlinck |IDWID BV| [email protected]