Written by David L. Shrier and A. Aldo Faisal

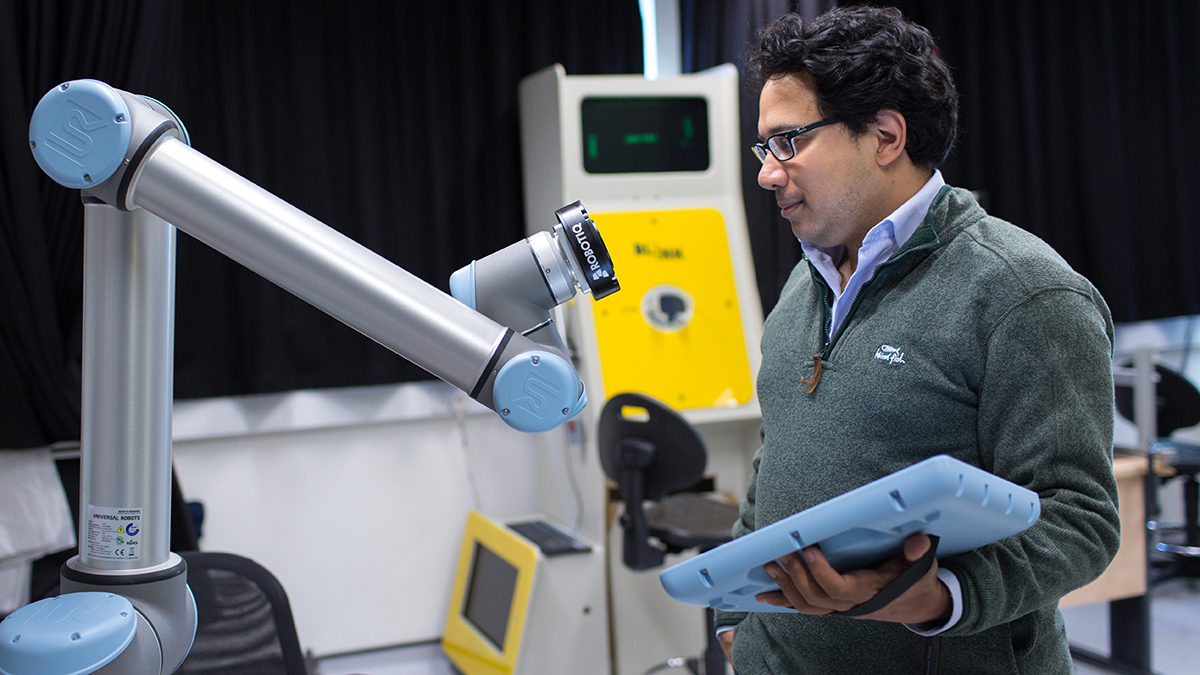

Aldo Faisal, Professor of AI and Neuroscience, Imperial College London

Generative AI has potential to deliver extraordinary abundance, perhaps doubling global GDP growth over the next 10 years, as well as dramatically transforming how white collar work is performed. At the same time, Generative AI may have a materially adverse impact on labour and economic prosperity in developing economies – affecting countries that previously prospered from trends such as outsourcing, digitization and upskilling. From Philippines to India to Bulgaria, from Kenya to Chile, there are no safe havens. A number of nations around the globe are taking action to address the impact of AI on their sovereign interests.

Flash Growth and New Risks

AI advances and its adoption in the past 18 months has been so rapid it has been termed “flash growth”. With this rapid adoption, it has been noted that perhaps half a dozen Big Tech companies not only control access to this transformational technology, but are directly delivering a Silicon Valley-centric brand of thought. A very small number of individuals are making key decisions about what goes into and what is expressed by Large Language Model (LLM) systems like ChatGPT or Gemini.

New risks are emerging; for example, if a particular country is home to global AI technology, what impact do its policies, such as export controls and tariffs, have on access to AI systems that are becoming essential to national interest? Economic and social development are thus at risk, by reversing capacity building and instead making countries dependent on ‘black box’ systems delivered by Big Tech. Similarly, Generative AI systems have to be educated, a bit like children, into what is and is not acceptable to say - thus putting into the hands of a few companies the determination of which ethical and societal values an AI system embodies.

Emerging Policy Action

Governments have taken note. In addition to new AI regulation and policy interventions (such as the EU AI Act and the US AI Executive Order), there are arising a series of sovereign AIs, which development and use are under a nation’s control. Billions of dollars US are now being allocated to the creation of large-scale AI systems that are independent of Big Tech by countries across Europe and Asia (Canada recently has weighed in, but it is unclear if they will pursue a fully sovereign AI).

Generative AI is the general-purpose AI technology that underpins not only LLMs, but also the ability to create “deep fake” videos and other content that can potentially reshape economies, or alter the course of public opinions and the numerous elections scheduled for 2024. A number of countries have begun to say, effectively, ‘we need to better manage these systemic risks’, as well as ‘we want to embed our local values, our national cultures into the GPTs that we use’.

Governments of multiple nations have expressed concern over unconscious bias, on the one hand, and unilateral design decisions, on the other hand, originating from Silicon Valley-based companies influencing the performance and outputs of commercially available GPTs. Creation of sovereign GPTs is a trend that potentially represents a democratization of AI, and a nuanced understanding of the effects of digital technology on society.

Overcoming Challenges

There remains the challenge that this is a rich country’s game. It can cost up to US$ 1 billion to build and train a new generative AI, and more to operate it at scale. Access to the chips which power these AI systems, tightly controlled by two Silicon Valley companies, further bottlenecks the ability of developing nations to engage in this domain. At this inflection point in history, there is the very real risk of widening the digital divide, creating a technology boom for the wealthy few at the expense of the many.

How can sovereign states pursue sovereign AI in an era of knowledge scarcity? Some of the technical aspects are widely disseminated, others, particularly on scaling up AI system training, are known to only a few thousand people in the world. To harness independent, neutral advice leading academic institutions are one of the best starting points. Obtaining access to the required vast scale of AI hardware is another challenge, both in terms of cost but crucially in the availability as Big Tech is consuming a substantial portion of annual production.

A federation of sovereign AI initiatives could bundle their respective midsized compute capacity to allow them together to each train an individuated model but with the benefits of scaled compute. The experience of the authors has shown that sovereign states also have unique advantages by being able to regulate safe and trustworthy AI use, and by having access to sovereign data and person-related data that may never be available to Big Tech. At Imperial College London, we are working to support sovereign AI initiatives being supported by our ecosystem of institutions and experts in the Trusted AI Alliance.

The Age of AI is upon us, with the power for great good by amplifying global prosperity – if we shape an enlightened path into this new era.

David Shrier is a Professor of Practice, AI and Innovation, with Imperial College London, where he leads the Trusted AI Alliance (a multi-university collaborative focused on safe & responsible AI) and is Academic Director of the Centre for Digital Transformation. His latest book, Basic AI: A Human Guide to Artificial Intelligence was published in 2024.

Aldo Faisal holds a prestigious UKRI Turing AI Fellowship, and is a Professor of AI & Neuroscience at Imperial College London and holds the Chair in Digital Health at the Universtät Bayreuth (Germany). He is director of the £50 million UKRI Centers in AI for Healthcare and AI for Digital Health in London. He is actively engaged in developing open source Generative AI systems.

Science, technology and innovation can be catalysts for achieving the sustainable development goals.

In the context of the UN Commission on Science and Technology for Development, the CSTD Dialogue brings together leaders and experts to address this question and contribute to rigorous thinking on the opportunities and challenges of STI in several crucial areas including gender equality, food security and poverty reduction.

The conversation continues at the annual session of the Commission on Science and Technology for Development and as an online exchange by thought leaders.